Introduction

On 7 March 1989, a decree imposing martial law on Lhasa was issued by Chinese Premier Li Peng and China’s State Council.

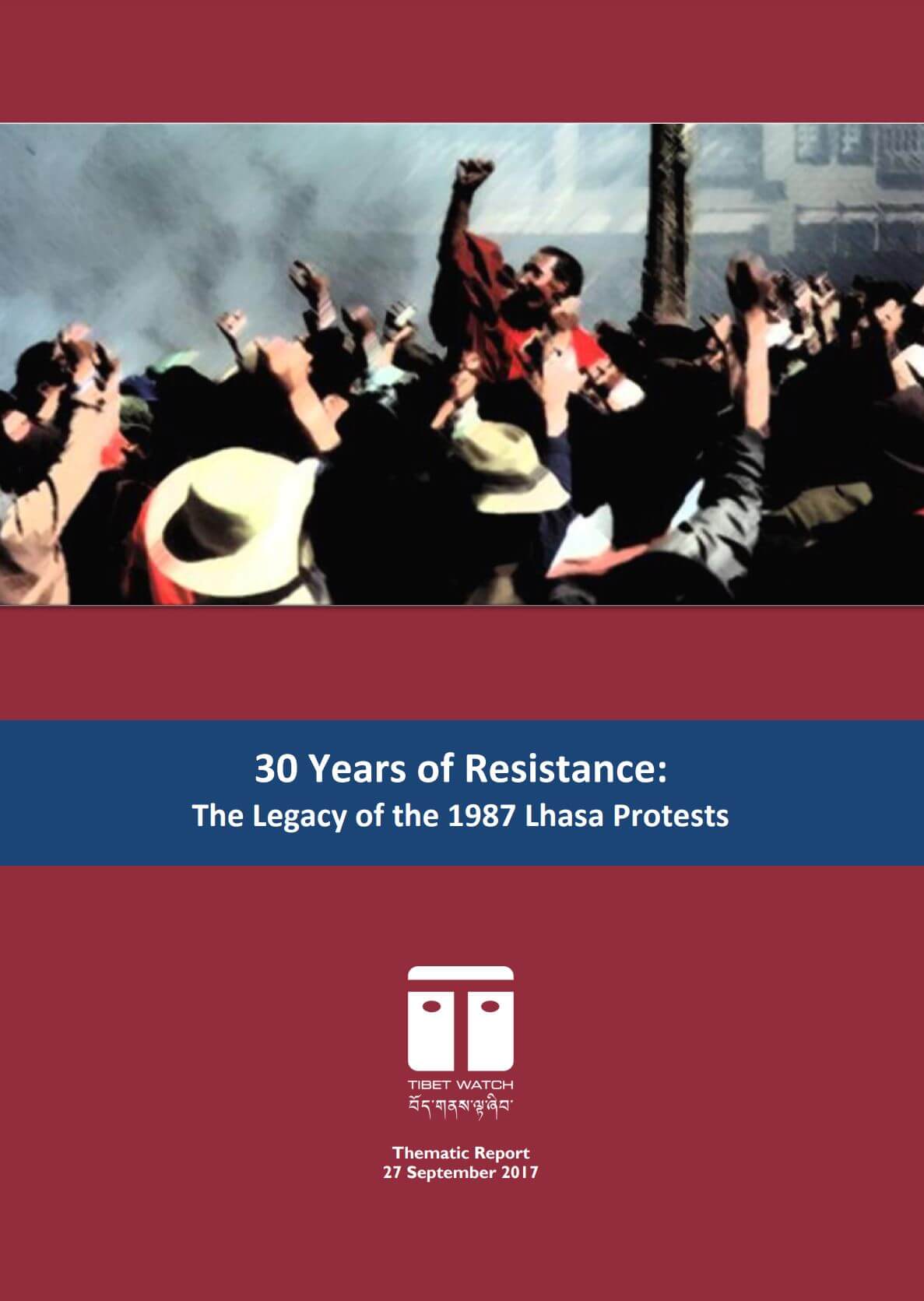

This move by Beijing firmly brought about a halt to a significant period of protest against Chinese rule in Tibet, led by monks from all three major monasteries in Lhasa: Sera Monastery, Drepung Monastery and Ganden Monastery. Until the protests in Lhasa in late 1987, carried out by the monks from Sera, Drepung and Ganden, Tibet had been a country forced into submission. When China started to invade in 1950, Tibetans all over Tibet resisted in various ways, including an armed resistance in eastern Tibet. The uprising in Lhasa in 1959 was crushed, however, and Tibet’s fate was sealed, despite armed resistance continuing with covert support from the USA.

After the Dalai Lama fled to exile in India in 1959, Tibet was closed off to the outside world for over two decades. The turbulent periods that shook China also shook Tibet, such as the Cultural Revolution which started in 1966 and lasted for ten years. Even before the Cultural Revolution had started though, all but 70 of the 2,500 monasteries in central Tibet had been closed for at least three years. 1 In 1978, the Chinese leadership, now under Deng Xiaoping following the death of Mao, changed policy and acknowledged some of its previous errors. In late 1979, a Tibetan delegation from Dharamsala, which included the Dalai Lama’s elder brother, Gyalo Dhondup, was allowed to visit Tibet.

Miscalculating the feelings of the Tibetan people, Ren Rong, then Party Secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region, had reported that there was no longer any support for the Dalai Lama and that Tibetans supported Communism. However, as the delegation reached Lhasa, “tens of thousands of Lhasa Tibetans mobbed the delegation in a huge display of affection and jubilation. Braving arrest, Tibetans in the crowd shouted out ‘Long live the Dalai Lama’ and ‘Tibet is independent’”. Subsequent visits from fact-finding delegations provoked a similar response and the fourth one, scheduled to leave in August 1980, was indefinitely postponed by China.

The next key turning point was a visit to Tibet by a Chinese central government delegation in May 1980, led by Party Secretary General and Politburo Standing Committee member Hu Yaobang. According to American scholar Ronald D Schwartz, Hu was shocked by what he found. He went on to make a series of recommendations for a new policy which then became the basis for the reforms in Tibet during the 1980s. This period of leniency in the 1980s was significant: “Many Tibetan religious and traditional customs were allowed again. A significant number of Tibetans were allowed to take up positions of some social status, to obtain education in universities, to study Tibetan culture, to travel abroad, and even, until 1985, to travel to India to meet the Dalai Lama. Tourism was permitted, and the Tibetan language was encouraged in primary schools. Publications in Tibetan boomed, monasteries reopened, and foreign films were shown on television.” 4 In 1980 Ren Rong was replaced by long-time PLA Commissar in Tibet Yin Fatang. In 1985 Yin Fatang was replaced by outsider and reformer Wu Jinghua, a protégé of Hu Yaobang’s. As Ronald D Schwartz notes, “Wu was committed to implementing the policy of ‘openness and reform’ in Tibet, and supported programmes to restore Tibetan culture, religion, and language.”Robert Barnett, Lhasa: Streets with Memories, Columbia University Press, 20

Tourism boomed during this period. Citing official Chinese statistics, the New York Times reported in April 1988 that 43,500 foreigners visited Tibet in 1987, spending more than USD 15 million. New luxury hotels were built in Lhasa by international companies such as the Holiday Inn. According to Robert Barnett, “the reforms did create an opportunity for rebuilding from the ground up the rudiments of a Tibetan civil society devastated by two decades of communism.”

The first three protests against Chinese rule in Lhasa were led by local monks and all took place within a ten-day period in the autumn of 1987. This report covers those protests and the subsequent ones which continued until Martial Law was decreed in March 1989.

Hu Jintao, then Party Secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region, issued five subsequent Martial Law Decrees in Lhasa over the next few days after the initial decree on 7 March 1989. Troops from the People’s Liberation Army poured into Lhasa that month, imposing checkpoints every few metres in the city. Prisoners were rounded up and given harsh sentences. Foreigners were expelled. Although martial law was to rule the city for 13 months, it was unable to quell protests for long. While the Lhasa protests of 1989 are fairly well known and leaked CCTV footage of the brutality of China’s response circulated internationally, less is known, generally, about the protests that originated in September 1987 and continued throughout 1988. However, photographic documentation does exist from these protests although, so far, very little of it has been made public, mainly for security reasons.

A few years ago a set of photographs taken during the 1987 and 1988 protests was acquired by one of Tibet Watch’s researchers from a late relative who had previously worked in the Department of Security in the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA). There were no notes or any other information left with the photographs so the research team’s first step was to try and find out who had taken them and whether any of them had been published before. It soon became clear that many of the images were unpublished and that we potentially had an opportunity to share new material from some of the earliest protests of the 1980s.

It was equally clear, however, that these photographs could not simply be published without additional research and verification. We wanted to find out the story behind each of the images but we also wanted to find out whether any of the individuals in the photographs were still alive and whether they or their families would be affected by publication. Some of the photographs from the original set have been withheld as a result of that investigation.

Throughout this process we worked closely with the CTA’s Department of Security, who recently provided some additional images, and with the Gu Chu Sum Movement Association of Tibet. We would like to thank them both for their cooperation and their input to this report. In addition to researching the photographs, Tibet Watch has been able to interview eyewitnesses and participants of the protests and hopes to present, through images and text, a comprehensive account of the turbulent and historic period in Lhasa between September 1987 and March 1989.